U.S. Tariffs, Media Narratives, and Economic Reality: A Critical Review

This in-depth post explores the overlooked history and modern relevance of U.S. tariffs, challenging mainstream media narratives and unpacking the economic impacts of free trade. From rising income inequality to the consolidation of media ownership, the article critically examines how policy, perception, and power intersect—backed by data-driven visuals and historical context.

U.S. Tariffs, Media Narratives, and Economic Reality: A Critical Review

Introduction

The topic of tariffs in the United States has become highly politicized in modern discourse, often accompanied by a media narrative that casts American tariffs as inherently negative or hostile to the global economy. This paper critically examines that narrative against historical and economic evidence. It argues that U.S. tariffs have long been a normal policy tool (much as they still are for many other nations), and that the decline of tariffs since the late 20th century correlates with rising domestic inequality. Potential reasons for media bias against tariffs – including corporate ownership of news outlets and vested interests in free trade – are explored. The analysis also critiques the free trade orthodoxy, suggesting that while it yields cheaper consumer goods in the short run, it may undermine long-term national interests such as industrial capacity, equitable income distribution, and even national security.

Historical Role of Tariffs in the United States

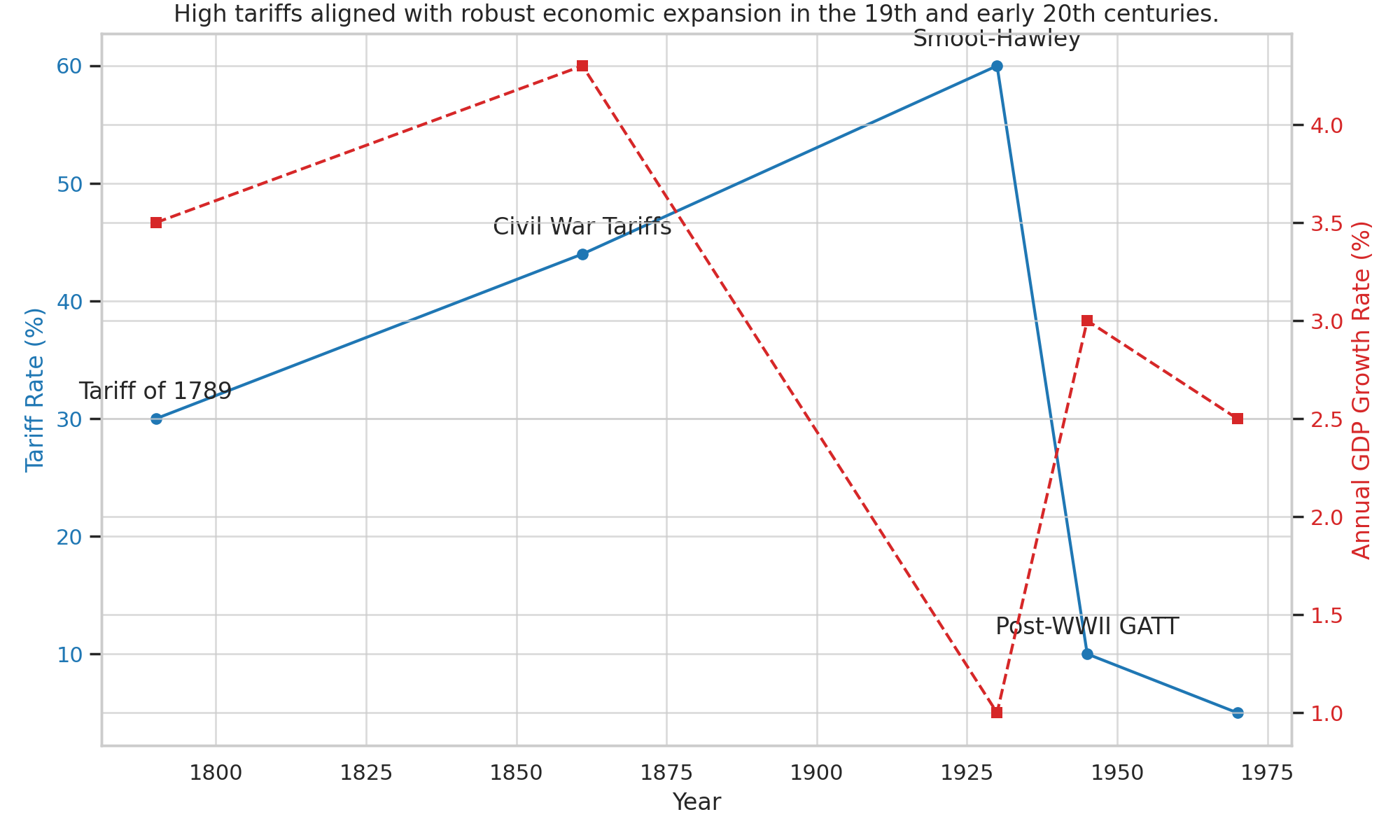

Historically, the United States was built on tariffs as a core element of its economic policy (Bartash, 2018; Rechenberg, 2024). From the nation’s founding through the 19th and early 20th centuries, high import tariffs were standard and served two main purposes: raising government revenue and protecting nascent American industries from foreign competition (Rechenberg, 2024). One of the first acts signed by President George Washington was the Tariff of 1789, designed to both fund the federal government and “protect early-stage American industries” (Rechenberg, 2024). During the 19th century, average U.S. tariffs on manufactured goods often exceeded 40%, making America one of the most protectionist nations at the time (Rechenberg, 2024). This protectionist period coincided with rapid industrial growth: between 1871 and 1913, when tariffs never fell below about 38%, the U.S. economy grew at an average annual rate of 4.3%, a pace well above later 20th-century trends (Howe & Rusling, n.d.). High tariffs were thus integral to the “American System” of economic development, which leaders like Alexander Hamilton and Henry Clay championed to foster domestic manufacturing (Magness, 2019).

Figure 1: U.S. Tariff Rates and GDP Growth, 1790–1970. High tariffs aligned with robust economic expansion in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Source: Howe & Rusling (n.d.), Rechenberg (2024).

Figure 1: U.S. Tariff Rates and GDP Growth, 1790–1970. High tariffs aligned with robust economic expansion in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Source: Howe & Rusling (n.d.), Rechenberg (2024).

Prominent American statesmen openly supported protective tariffs. For example, Alexander Hamilton argued in his 1791 Report on Manufactures that while free trade might be ideal in a world where all nations played by the same rules, that was not the reality. “If the system of perfect liberty to industry and commerce were the prevailing system of nations,” Hamilton wrote, “free trade would have merit. But the system … is far from [that] … The prevalent one has been regulated by an opposite spirit” (Hamilton, 1791, as cited in Magness, 2019). In other words, because European powers heavily protected their own industries, Hamilton believed the United States also needed tariffs to level the playing field. Decades later, President Abraham Lincoln echoed this sentiment. An early Lincoln speech declared: “I am in favor of … a high protective tariff. These are my sentiments and political principles” (at a time when Lincoln aligned himself with Henry Clay’s protectionist American System) (Rechenberg, 2024). He is even reputed to have said in 1847: “Give us a protective tariff, and we will have the greatest nation on earth” (Rechenberg, 2024). Lincoln’s administration indeed raised tariffs to historically high levels (around 44%) during the Civil War, using them to fund the war effort and nurture Northern industry (Howe & Rusling, n.d.).

A later president, Ulysses S. Grant, reflected in the 1870s on Britain’s example with a shrewd prediction: “After two centuries, England has found it convenient to adopt free trade… My knowledge of our country leads me to believe that within 200 years, when America has gotten out of protection all that it can offer, it too will adopt free trade” (Rechenberg, 2024). This quote underscored that protection had benefited Britain’s rise—and Grant implied the U.S. should likewise use tariffs until it no longer needs them. Such statements reveal that far from being aberrations, tariffs were once mainstream policy supported by American founders and presidents as tools to build a “greatest nation” (Rechenberg, 2024).

By the mid-20th century, however, U.S. trade policy shifted. Following World War II, the United States led efforts to lower tariffs globally (through the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, later the WTO) in pursuit of freer trade (Rechenberg, 2024). Tariff rates that had averaged well above 30% in the 1920s were brought down into the single digits after 1945 (Rechenberg, 2024). This represented a sea change in thinking: the infamous Smoot-Hawley Tariff of 1930 (which raised many rates to ~60%) had been blamed for exacerbating the Great Depression through retaliatory trade wars (Rechenberg, 2024). In reaction, post-war U.S. policymakers of both parties grew averse to protectionism (Rechenberg, 2024). By the 1970s, average U.S. tariffs had leveled off at around 5% or less (Rechenberg, 2024) – a remarkable drop from the highs of earlier eras. The United States embraced a paradigm of free trade under the assumption that its post-war industrial dominance would persist (Rechenberg, 2024).

Indeed, for a time American producers did flourish in the 1950s–1960s. But the landscape changed by the 1970s: countries like Germany and Japan had rebuilt their industries, and newly industrializing economies were emerging, leading to intense import competition. American industries, from steel to consumer electronics, began struggling against this foreign competition, now facing minimal tariff protection. As one retrospective notes, “the 1970’s marked the decline of US industry. Global competition from low-cost producers was too much to overcome and low import tariff rates offered no protection” (Howe & Rusling, n.d.). In other words, just as U.S. tariffs reached their nadir, domestic manufacturing found itself vulnerable. This period also saw the U.S. trade balance swing negative; the country became a net importer of goods on a large scale (Howe & Rusling, n.d.). The stage was set for economic and social repercussions that would become evident in the ensuing decades.

The Post-1970s Era: Tariffs, Trade, and Rising Inequality

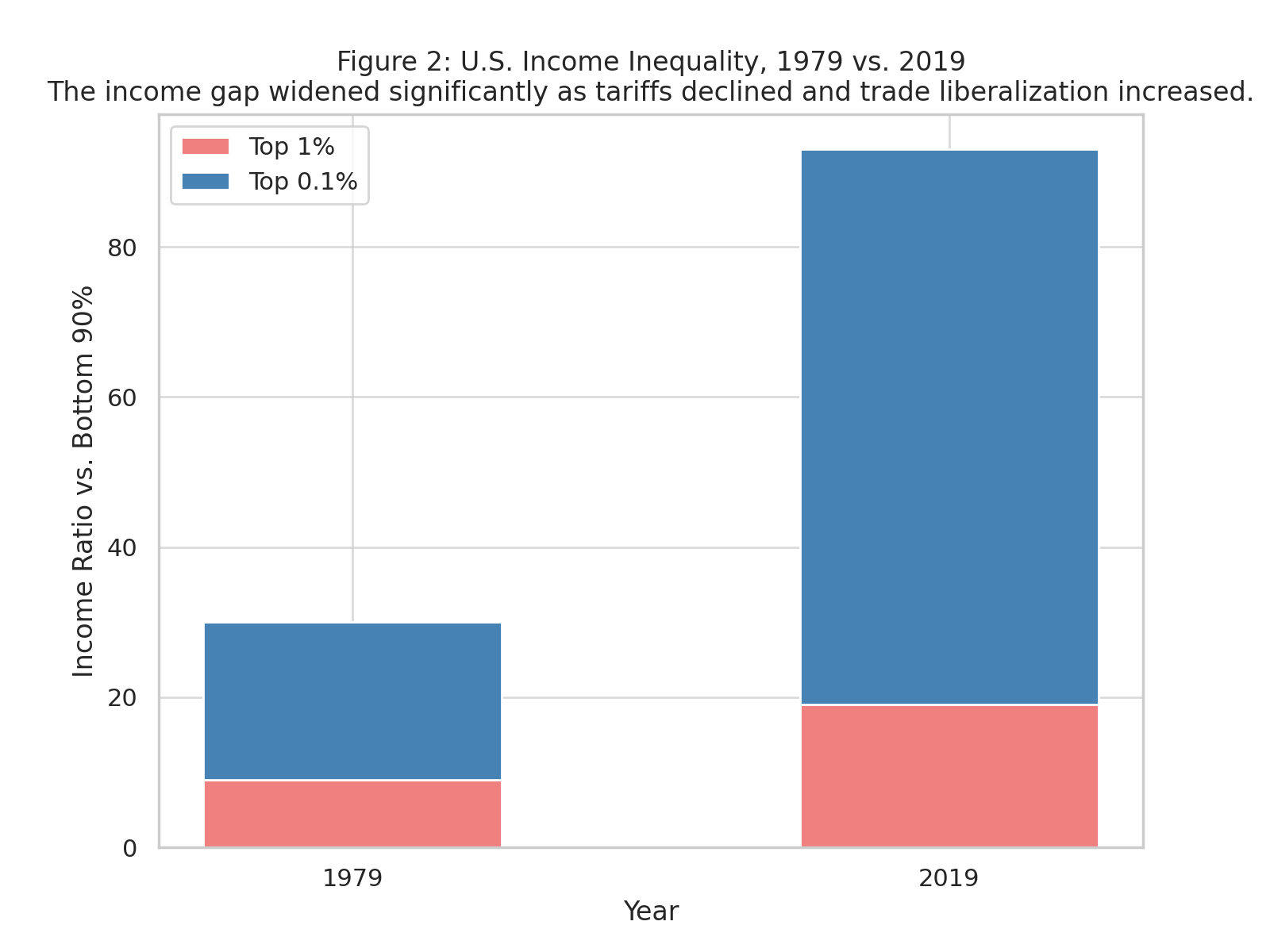

One striking trend since the late 1970s has been the steep rise in income inequality within the United States. Notably, this rise coincided with the era of trade liberalization and low tariffs. While many factors contribute to inequality, numerous economists have identified globalization and trade policy as significant drivers (Rechenberg, 2024). The timing is hard to ignore: roughly “since about 1980, the United States has suffered from increasingly worse income inequality,” after a period of relative equality in the mid-20th century (Rechenberg, 2024). In 1979, on the eve of widespread trade liberalization, the average income of the top 1% of Americans was about 9 times that of the bottom 90%. By 2019 – after decades of offshoring and free trade deals – the top 1% earned 19 times the income of the bottom 90% (and the top 0.1% earned 74 times as much) (Rechenberg, 2024). This dramatic widening is illustrated in Figure 2, which highlights how disproportionately the gains of the last 40 years have accrued to the very wealthy.

Figure 2: U.S. Income Inequality, 1979 vs. 2019. The income gap widened significantly as tariffs declined and trade liberalization increased. Source: Rechenberg (2024).

Figure 2: U.S. Income Inequality, 1979 vs. 2019. The income gap widened significantly as tariffs declined and trade liberalization increased. Source: Rechenberg (2024).

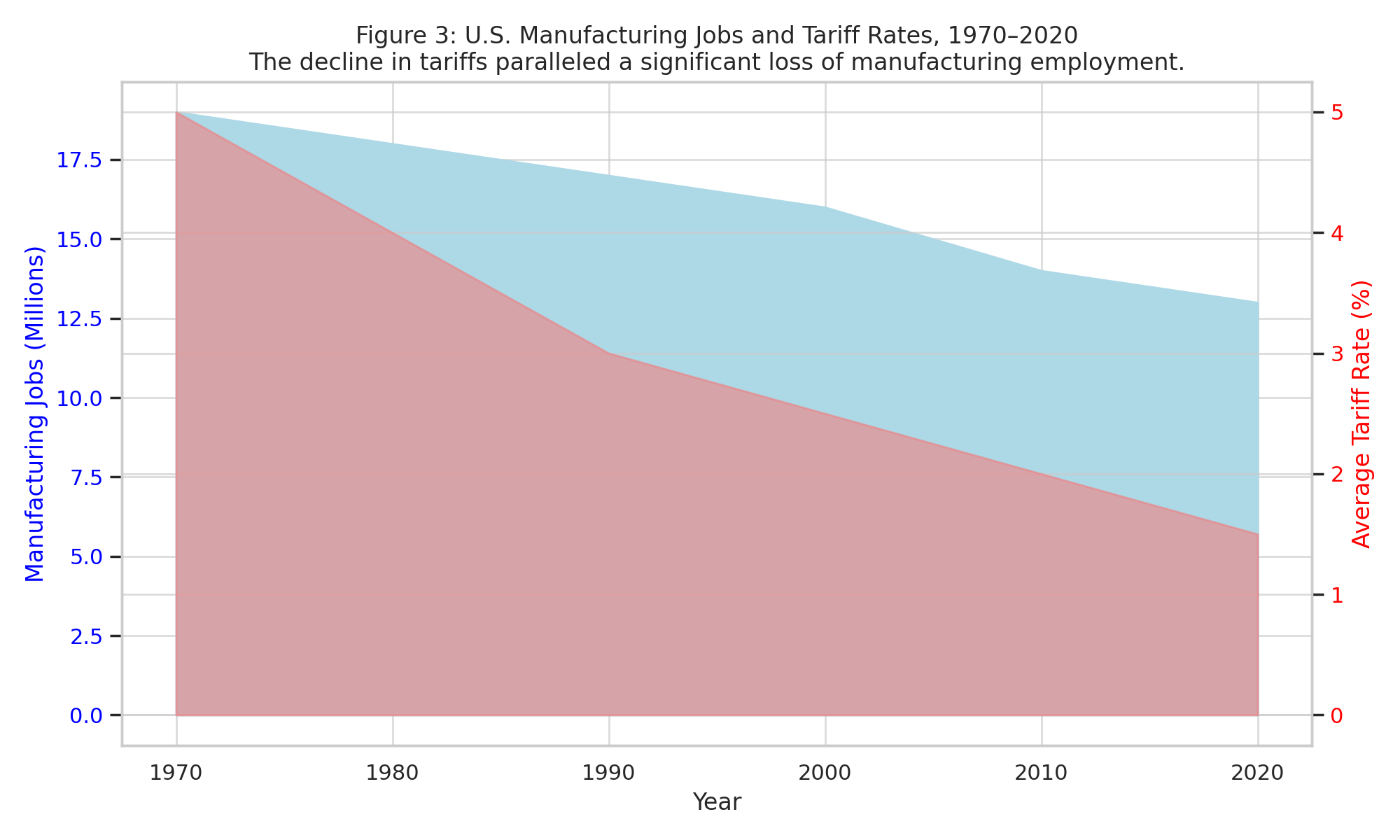

Multiple studies tie this inequality uptick in part to trade patterns. As tariffs fell and imports surged, many American manufacturing jobs disappeared, and wages stagnated for lower- and middle-class workers (Rechenberg, 2024). One National Bureau of Economic Research study found that competition from rising Chinese imports alone accounted for an estimated 2.0 to 2.4 million U.S. job losses from 1999–2011 (Rechenberg, 2024). These losses were concentrated in industries like furniture, textiles, and machinery – sectors that had been relatively protected or dominant in the pre-free trade era (Rechenberg, 2024). Crucially, the displaced workers often struggled to find comparably paying work; the new jobs available were typically in lower-wage sectors. Federal labor data underscore this: manufacturing jobs, which often paid over $34/hour on average, were replaced by jobs in retail or hospitality paying barely $22–24/hour (Rechenberg, 2024). The result is not only unemployment in certain regions but also a downgrading of income prospects for blue-collar workers nationally. In aggregate, the loss of high-paying factory jobs put downward pressure on the wage distribution, contributing to wider income gaps. It is telling that the share of national income going to labor (versus capital) has declined in this same period, while corporate profits (and the incomes of capital owners) surged – a trend consistent with companies moving production to low-wage countries. Indeed, empirical analyses have concluded that “the import channel is the dominant force linking trade to earnings inequality, with the largest gains from trade occurring at the top of the income distribution” (Rechenberg, 2024). (In other words, the benefits of cheap imported goods and global supply chains accrue primarily to investors and executives at the top.)

Figure 3: U.S. Manufacturing Jobs and Tariff Rates, 1970–2020. The decline in tariffs paralleled a significant loss of manufacturing employment. Source: Howe & Rusling (n.d.), Rechenberg (2024).

Figure 3: U.S. Manufacturing Jobs and Tariff Rates, 1970–2020. The decline in tariffs paralleled a significant loss of manufacturing employment. Source: Howe & Rusling (n.d.), Rechenberg (2024).

It is important to note that correlation is not causation – trade liberalization is not the sole cause of U.S. inequality. Technological change, domestic policy (like tax cuts favoring the rich), and weakened labor unions also played roles. However, trade policy clearly exacerbated inequality trends. A comprehensive meta-analysis by the Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies found that globalization tended to increase income inequality in both advanced and developing countries on average (Rechenberg, 2024). And within the U.S., regions most exposed to import competition experienced not only greater job and wage loss, but also secondary social effects such as higher crime rates and worse health outcomes (Rechenberg, 2024). Those broad impacts hint that the hollowing-out of industry in many communities (the Rust Belt being a prime example) has had profound societal costs. In contrast, those positioned to profit from globalization – e.g., owners of capital and multinational enterprises – have reaped considerable gains. It has been observed that “the top 1–10% have been the primary benefactors of increased trade and imports into the United States” (Rechenberg, 2024). This dynamic is reflected in the wealth data: the top 1%’s share of U.S. net wealth rose from about 23% in 1990 to over 30% by 2020 (Rechenberg, 2024), partly because globalized firms delivered higher returns to shareholders even as worker wages stagnated.

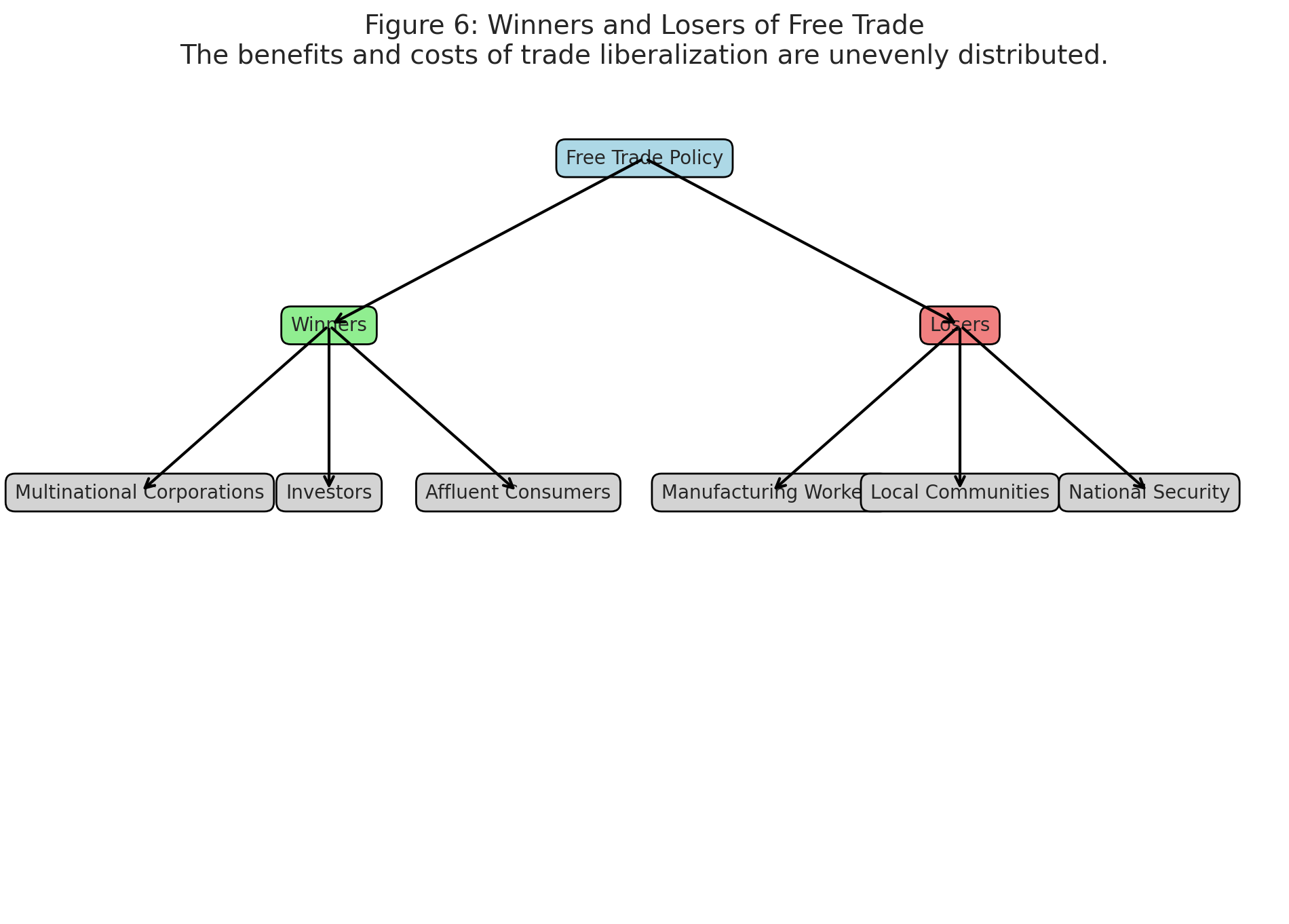

In summary, the decline of tariff protection since the late 1970s correlates with a period of rising inequality and industrial decline in the U.S. While free trade brought consumers an abundance of cheaper goods, it also contributed to factory shutdowns, job offshoring, suppressed wage growth, and greater income stratification. The “managed trade liberalization” of the past decades was not an unequivocal win for the broad American middle class – instead, it produced clear winners and losers. The winners tended to be those with the mobility and capital to leverage global markets (investors, large corporations, and highly skilled professionals), whereas many average workers and their communities saw adverse effects (Rechenberg, 2024).

Modern Media Coverage: Ownership and Bias in Trade Reporting

Despite the nuanced reality of trade-offs surrounding tariffs, much of the contemporary media coverage presents tariffs in a consistently negative light. U.S. news outlets often frame tariff proposals as economically harmful on the whole, with headlines warning of trade wars, higher consumer prices, and upset international allies. For instance, when new tariffs were imposed in 2018, an Associated Press explainer opened by saying “Trump’s long-threatened tariffs are here, plunging the country into an escalating trade war…” and warned that experts predict consumers will be “the hardest hit,” facing price hikes on everything from cars and appliances to everyday groceries (Grantham-Philips, 2018). The clear message in such reporting is that tariffs = higher costs for Americans, with little mention of any offsetting benefits. Similarly, many outlets emphasized retaliatory moves by other countries, reinforcing the notion that any U.S. tariff action is a destructive act inviting economic pain on all sides (Grantham-Philips, 2018).

While it is true that tariffs can lead to retaliation and raise consumer prices in the short run, the singularity of this framing – focusing almost exclusively on tariffs’ downsides – suggests a strong editorial bias. Reports rarely note that America’s trading partners routinely use tariffs to protect their own industries (making U.S. action sometimes a response rather than unprovoked aggression). For example, in the beef sector, Japan raised its tariff on certain U.S. beef imports to 50% after the U.S. withdrew from a trade pact, a fact that underscores how other nations are willing to shield their markets when it suits their interests (Baker, 2017). Likewise, China has long levied higher average tariffs than the U.S. on many categories of goods, yet media narratives seldom criticize foreign protectionism with the same vigor directed at American tariffs. This asymmetry – treating U.S.-imposed tariffs as scandalous, but foreign-imposed barriers as business-as-usual – points to a skew in perspective.

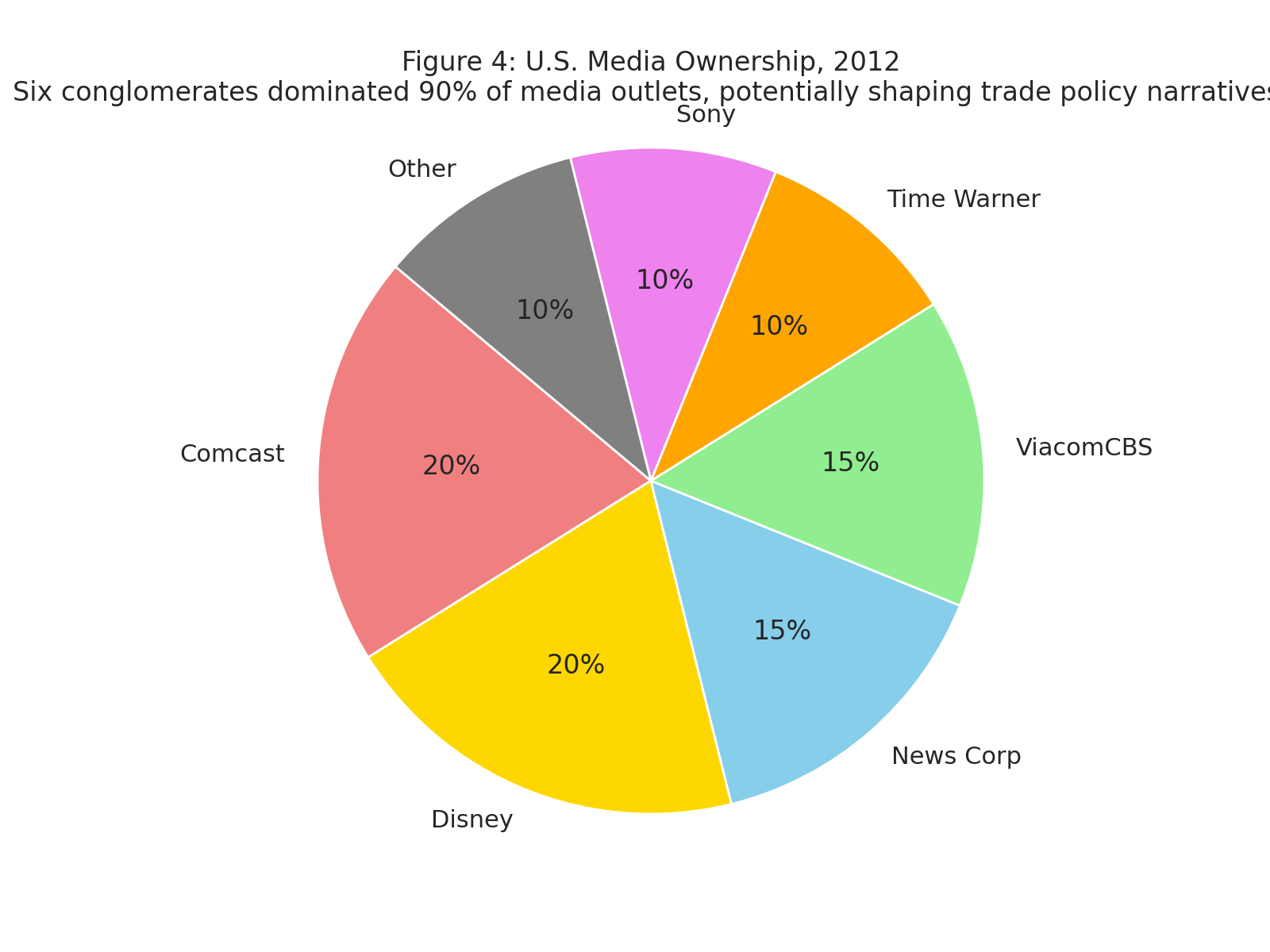

Why might the U.S. media broadly push a pro-free-trade, anti-tariff narrative? One explanation lies in media ownership and sponsorship. Over the past few decades, American media has consolidated into the hands of a few large conglomerates. By 2012, it was reported that almost 90% of U.S. media outlets (newspapers, TV, radio, etc.) were owned by just six corporations (Business Insider, 2012). These parent companies (such as Disney, Comcast, News Corp, ViacomCBS, etc.) are themselves global enterprises with extensive international investments and markets. Their executives and advertisers often come from the same class of multinational business interests that benefit from the free flow of goods and capital across borders. It stands to reason that such media owners might be averse to tariffs, which could disrupt global supply chains or reduce corporate profits on imported consumer goods. Even when not an explicit top-down directive, this bias can manifest in subtler ways – through the experts journalists choose to quote, the economic assumptions they take for granted, and the story angles they pursue.

Figure 4: U.S. Media Ownership, 2012. Six conglomerates dominated 90% of media outlets, potentially shaping trade policy narratives. Source: Business Insider (2012).

Figure 4: U.S. Media Ownership, 2012. Six conglomerates dominated 90% of media outlets, potentially shaping trade policy narratives. Source: Business Insider (2012).

Major news outlets also depend on advertising revenue from large corporations (think of auto companies, tech giants, big retailers), many of whom rely on cheap imports for their products or inventory. It is not surprising, then, that coverage often mirrors the talking points of those industries (e.g., emphasizing consumer price increases or export losses) while downplaying arguments about protecting jobs or industries. As media watchdog analyst Dean Baker observed, there is a tendency in corporate media to present the failure to sign free trade deals as an unmitigated “economic disaster,” even when evidence for such claims is thin (Baker, 2017). He notes cases where outlets touted minuscule projected gains from trade agreements as vital to “saving” sectors like agriculture, without offering context that those gains were almost negligible (Baker, 2017). This reflects a pro-trade ideology in newsrooms – one that aligns neatly with the interests of the business elites who own and finance those news platforms.

Media consolidation can thus lead to narrative homogenization. When only a handful of corporate entities control most channels of information, a narrow economic worldview can dominate. In the realm of trade policy, that dominant view has been staunchly pro-free-trade. Dissenting perspectives – such as labor leaders or heterodox economists who support selective tariffs – receive comparatively little airtime or are often portrayed as fringe. Studies have shown that U.S. media, especially in the 1990s–2000s, tended to marginalize critics of NAFTA, WTO, and other free trade policies, while giving ample space to pro-trade voices. The result is a public perception that virtually all experts oppose tariffs, when in fact there has been robust debate. The potential conflict of interest inherent in media conglomerates covering issues that affect their own shareholders’ profitability is seldom acknowledged in news coverage. For example, a network owned by a conglomerate that relies on Chinese manufacturing might not highlight stories of factories closing due to import competition – or may frame the issue as an unavoidable outcome of progress, rather than questioning trade policy. In essence, the media’s economic reporting may reflect the “worldview of their owners,” who are among the wealthy cosmopolitan class that benefits from global trade (Baker, 2017).

It is also worth noting that the simplicity of the free trade narrative – “tariffs bad, free trade good” – is convenient for media soundbites. Explaining the nuanced historical or distributional effects of tariffs takes effort and does not fit neatly into a headline. It is far easier to run a story like “Tariffs likely to cost American families $X this year in higher prices” than to explore how targeted tariffs might save certain industries or jobs. The latter would require a deeper, more investigative approach (for instance, looking at a Midwestern town before and after a steel mill closure). In the fast-paced news cycle, economic nuance often loses out to clear-cut claims, and the claim that “tariffs hurt the economy” is repeated so often that it becomes almost axiomatic. Meanwhile, stories of other countries’ routine protectionism (say, European agricultural tariffs or China’s technology-transfer rules) are typically confined to the business pages or framed as isolated disputes, rather than pieces of a larger pattern. The cumulative effect is a pro-liberalization bias: trade agreements are lauded as “wins” or “historic,” whereas tariff measures are labeled “populist” or “provocative.” None of this is to suggest a grand conspiracy, but rather the predictable outcome when media industries are tightly interwoven with other elite economic interests. As one commentary wryly put it, mainstream outlets have little incentive to question free trade because “those corporate advertisers … are what keeps those outlets operating” (Baker, 2017). In sum, the structure of media ownership and the incentives of profit-driven news help explain why the prevailing narrative tends to favor free trade and cast protectionist policies in a negative light.

Free Trade Orthodoxy vs. National Interest – A Critique

Free trade has undeniable benefits: it can lower consumer prices, expand the variety of goods available, and foster international cooperation. These benefits largely explain why the U.S. and other nations moved toward trade liberalization after World War II. However, the orthodox narrative that “free trade is always in the national interest” does not always hold up under scrutiny. This section critiques that narrative, highlighting ways in which unrestrained free trade may conflict with a country’s long-term economic and security interests.

Firstly, the promise that free trade would “lift all boats” in the U.S. economy has proven incomplete at best. While aggregate economic output grew, the gains were very unevenly distributed (as documented earlier). Consumers enjoyed cheaper apparel, electronics, and other imports, but the communities that lost factories paid a heavy price. There is a long-term social cost to deindustrialization that pure economic models often ignore: once a factory closes, the ecosystem of jobs and skills around it withers. Entire regions can enter a downward spiral of unemployment, depopulation, and despair – outcomes that threaten national cohesion. By contrast, tariffs (or other protective measures) can serve as a tool to sustain key industries and jobs, especially in sectors vital for middle-class employment. For example, tariffs on steel or auto imports can help keep domestic steel mills and auto plants open, preserving jobs that pay decent wages to workers without advanced degrees. A free trade advocate might counter that those workers eventually find new jobs in other sectors, but in reality many do not find equally good jobs, contributing to the kind of income polarization the U.S. has experienced (Rechenberg, 2024). Thus, what’s “free” trade for an economist on paper can feel like very unfair trade to a laid-off manufacturing worker in Ohio or Michigan.

Moreover, the national interest encompasses more than just consumer prices; it includes maintaining industrial capabilities that could be crucial in emergencies. The COVID-19 pandemic offered a stark lesson. In 2020, as global supply chains faltered, Americans faced shortages of personal protective equipment, medical supplies, and even basic consumer goods (Magness, 2019). Decades of offshoring production meant the U.S. lacked domestic capacity in many critical items – from N95 masks to certain pharmaceuticals – and was dependent on imports that were suddenly disrupted. This led to bipartisan calls to “reshore” production of essential goods, with even free-trade proponents like Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen endorsing targeted protectionist policies in the name of economic and national security (Magness, 2019). The episode underscored that a totally globalized supply chain, while efficient in normal times, can be dangerously brittle in a crisis. Countries like Japan and France, learning from the pandemic, began initiatives to bring some manufacturing back home for strategic reasons. The U.S. national interest similarly may require safeguarding certain industries (such as semiconductors, medical equipment, rare earth minerals, etc.) even if it means forsaking the lowest global price. Pure free trade ideology struggles to account for these security externalities. Tariffs or quotas can be blunt instruments, but they are one way to incentivize domestic production of things a nation deems critical for resilience.

Free trade orthodoxy also often assumes that all countries play by the same rules and that market forces alone should dictate outcomes. In reality, many countries actively pursue mercantilist strategies – using tariffs, subsidies, and other tools – to build up their own industries (much as the U.S. did in the 19th century). China is the premier example in recent times: it joined the WTO in 2001 and benefited from access to Western markets, but it also leveraged state power to protect and promote Chinese firms. Intellectual property theft, forced technology transfer, and hefty subsidies to strategic sectors (like solar panels and telecommunications) were all part of China’s rise as a manufacturing powerhouse. American free trade advocates were caught off guard by the speed and scale of China’s manufacturing ascent, which was facilitated in part by China’s non-market policies. In such an environment, sticking rigidly to free trade principles can amount to unilateral disarmament. If one’s trading partner is imposing hidden tariffs (through currency manipulation or industrial subsidies, for instance), a refusal to counteract these measures may harm one’s own industries. This is precisely what Hamilton argued back in 1791 – and his logic remains relevant (Hamilton, 1791, as cited in Magness, 2019).

Modern proponents of strategic or “fair” trade argue that some tariffs can be used as leverage to push partners toward reciprocity or to counteract distortions. Indeed, the U.S. government under several administrations has maintained targeted tariffs on certain imports (e.g., antidumping duties on steel) for these reasons, even while broadly advocating free trade. This suggests an implicit acknowledgment that a simplistic free-trade-at-all-costs stance is not always in the national interest. The White House itself noted that the United States, despite being one of the most open economies, must sometimes use tariffs as a “powerful, proven source of leverage for protecting the national interest” (The White House, 2025).

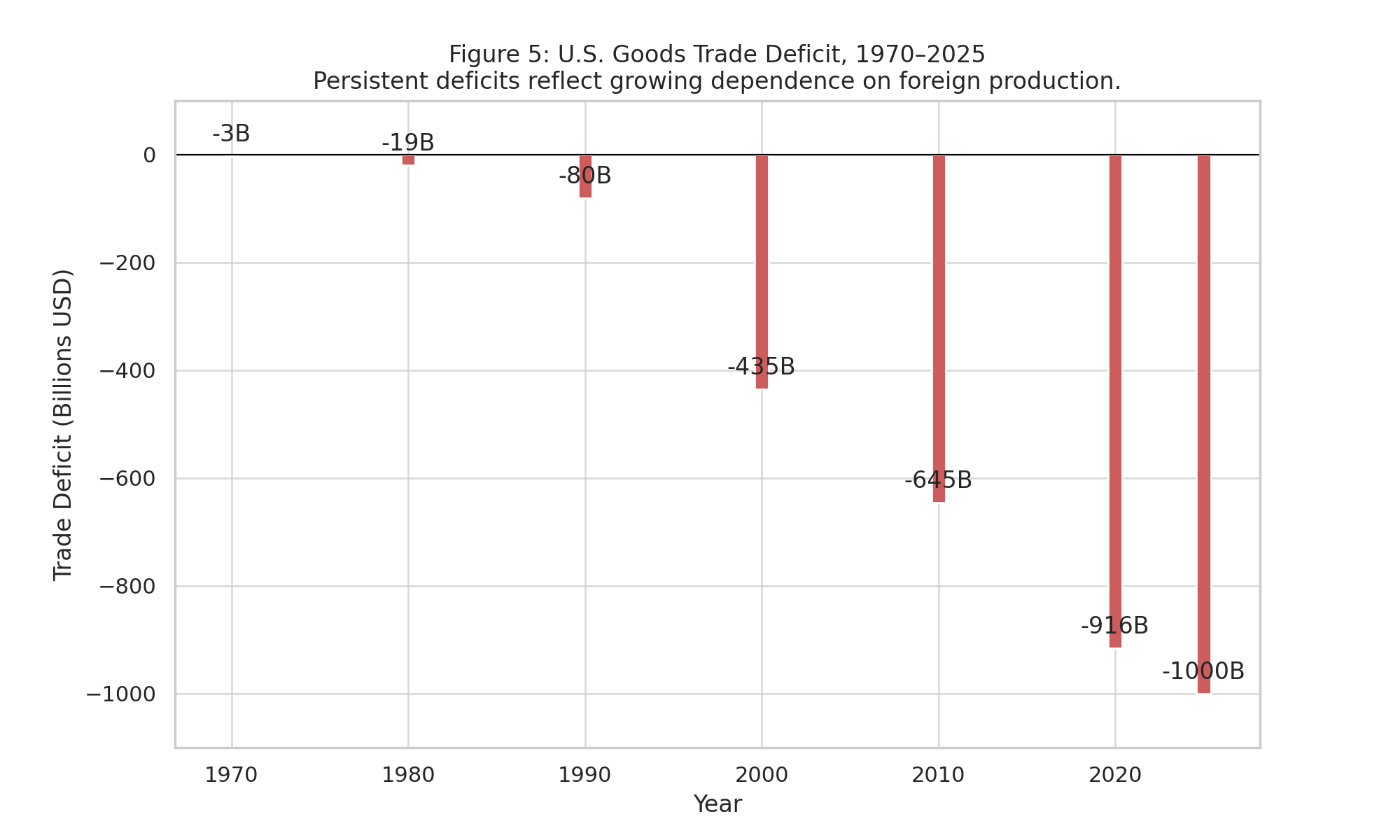

Another aspect often glossed over in the free trade narrative is the trade deficit. The U.S. has run persistent trade deficits for decades (importing far more than it exports), reaching over $1 trillion in goods deficit in recent years (The White House, 2025). While many economists downplay the significance of trade deficits (viewing them as a result of investment flows or macroeconomic factors), they do indicate a reliance on foreign production to meet domestic demand. Continuous large deficits in manufactured goods correspond to the loss of domestic market share for American producers. Some observers worry that this erodes the industrial base and increases vulnerability. For instance, if the U.S. no longer makes certain electronics or machine tools, it must depend on others for them, potentially hampering self-sufficiency. Free trade theory says each nation should specialize in what it’s most efficient at – and for the U.S., that has meant specializing less in manufacturing and more in services and high-tech innovation. But national interest is a broader concept than narrow efficiency; it includes sustaining well-paying jobs for citizens and the capacity to produce essential goods. A more balanced trade approach, possibly including tariffs or export incentives, might yield smaller deficits and a stronger manufacturing sector, at the cost of some consumer price increases. The media narrative rarely entertains this trade-off. Instead, it typically frames any deviation from free trade as risking “economic efficiency” without asking for whom the economy is being made efficient. As things stand, it has been highly efficient at rewarding capital (via cheaper inputs and labor abroad) while perhaps being inefficient at preserving equitable prosperity at home.

Figure 5: U.S. Goods Trade Deficit, 1970–2025. Persistent deficits reflect growing dependence on foreign production. Source: The White House (2025).

Figure 5: U.S. Goods Trade Deficit, 1970–2025. Persistent deficits reflect growing dependence on foreign production. Source: The White House (2025).

Finally, the beneficiaries of free trade deserve scrutiny. As noted, the greatest benefits of the status quo accrue to those able to arbitrage global labor and environmental differentials – essentially, large multinational corporations and their investors. These entities can produce goods in low-cost countries, then sell into the rich U.S. market at much higher margins. American consumers do save money from this arrangement (buying low-priced imported goods), but one might ask: at what cost? If the savings are outweighed by losses in wages and employment for those same consumers (now working in lower-paying jobs), the net national gain is dubious. Moreover, the consumer savings themselves often flow to retailers and middlemen: for example, a $5 shirt from a sweatshop may still be sold for $20 by a U.S. brand – the brand captures profit even as the manufacturing worker’s wage is squeezed. In this sense, free trade can act like a regressive transfer: benefitting owners and affluent consumers more than workers. The media narrative that “free trade is good for everyone” masks these distributional concerns. It portrays the issue as enlightened globalism vs. parochial protectionism, rather than acknowledging that free trade produces winners (often the wealthy) and losers (often the working class) (Rechenberg, 2024). Tariffs, in turn, are often dismissed as merely raising prices, when they could also be viewed as a tool to shift some profit share from foreign producers back to domestic producers and workers.

Figure 6: Winners and Losers of Free Trade. The benefits and costs of trade liberalization are unevenly distributed. Source: Rechenberg (2024).

Figure 6: Winners and Losers of Free Trade. The benefits and costs of trade liberalization are unevenly distributed. Source: Rechenberg (2024).

In conclusion, a critical review of the free trade narrative reveals that unalloyed free trade is not automatically synonymous with the national interest. Judicious use of tariffs and trade policy can, in certain contexts, bolster a nation’s economic health – by protecting vital industries, preventing excessive inequality, and ensuring readiness for crises. Even many economists concede that some degree of protection can be warranted (e.g., the concept of protecting “infant industries” until they become competitive). The U.S. itself used high tariffs to become the world’s leading industrial power by the 20th century (Rechenberg, 2024). The challenge today is finding the balance between openness and protection. The current media discourse, however, often fails to even recognize this as a legitimate debate, tending instead to equate any protectionism with economic folly. By reintroducing historical context and empirical evidence into the conversation, this paper has attempted to show that the reality is far more complex. Free trade has merits but also downsides, and tariffs – when used strategically – can be beneficial. A more nuanced media narrative would serve the public better, one that treats tariffs as a policy tool (like interest rates or taxes) that can be good or bad depending on how they are used, rather than as an unequivocal evil.

Conclusion

The modern media depiction of U.S. tariffs largely paints them as destructive – a stark departure from the nation’s own rich history of using tariffs to foster growth and prosperity. This paper has provided a detailed examination that challenges that one-dimensional narrative. Historically, tariffs were a pillar of American economic strategy from the early Republic through World War II, endorsed by figures ranging from Alexander Hamilton to Abraham Lincoln (Hamilton, 1791, as cited in Magness, 2019; Rechenberg, 2024). The late 20th-century experiment in broad free trade coincided with significant domestic costs, including rising income inequality and the loss of industrial capacity, even as it delivered cheaper goods and higher corporate profits (Rechenberg, 2024). Media coverage, influenced by corporate ownership structures and a pro-globalization ethos, often overlooks these complexities (Baker, 2017; Business Insider, 2012). Instead, it tends to amplify the perspectives of those who benefit most from free trade (large multinational businesses and wealthy consumers) while marginalizing those who voice the concerns of displaced workers or struggling industries.

A more balanced understanding of tariffs recognizes that they are neither panacea nor poison in themselves. Tariffs can protect communities and strategic industries – or, if misused, they can invite inefficiency and retaliation. Likewise, free trade can spur growth and innovation – or it can undermine social stability and national security if taken to an extreme. Sound policy requires navigating these trade-offs based on evidence, not ideology. The near-uniform negativity of the media’s tariff narrative does a disservice by ignoring valid arguments in favor of tariff measures that many other countries regularly employ to their advantage. As the United States faces new challenges (from global pandemics to great-power economic rivalry), it may need the flexibility to use all tools at its disposal, including tariffs (The White House, 2025).

In closing, the critique advanced in this paper is not an argument for autarky or a wholesale return to 19th-century protectionism. Rather, it is an argument for intellectual honesty and breadth in how we discuss trade policy. The media, as a primary shaper of public opinion, ought to present tariffs in context – acknowledging that the U.S. thrived under higher tariffs for much of its history (Rechenberg, 2024), and that many economic success stories abroad have been built on strategic protection. By broadening the narrative, policymakers and the public can have a more informed debate on what mix of trade and tariff policies will truly serve the nation’s long-term interests. After all, the ultimate goal is widely shared prosperity and a robust, secure economy – a goal that free trade alone has not achieved in recent decades, and which a dogmatic media narrative cannot help achieve. A more nuanced media approach would treat tariffs not as taboo, but as one option in the policy toolkit – to be evaluated on their merits in specific situations. History and data suggest that, used wisely, tariffs can contribute to economic strength, just as surely as indiscriminate free trade can sometimes weaken it. The hope is that future discourse on this issue becomes more balanced, reflecting the full complexity of how trade, tariffs, and national well-being intersect.

References

- Baker, D. (2017, August 11). Do Corporate Media Need to Lie to Promote Trade Deals? FAIR. Retrieved from Common Dreams

- Bartash, J. (2018, August 16). Trump is right: America was ‘built on tariffs’. MarketWatch. Retrieved from https://www.marketwatch.com (via Coalition for a Prosperous America).

- Business Insider. (2012). These 6 Corporations Control 90% Of The Media In America. Business Insider.

- Grantham-Philips, W. (2018). What to know about Trump’s tariffs and their impact on businesses and shoppers. Associated Press News. Retrieved from https://apnews.com/article/trump-tariffs-explainer-399b5d4da6e6be77cefabf25ceaa8191

- Hamilton, A. (1791). Report on the Subject of Manufactures. (Extract quoted in: Magness, P., 2019, Alexander Hamilton, the Other Tariff Man Who Created a Mess, The Daily Economy.)

- Howe & Rusling. (n.d.). Tariffs in America: A Look Back at Their Impact on the Economy. Retrieved from https://www.howeandrusling.com/tariffs-in-america-a-look-back-at-their-impact-on-the-economy/

- Magness, P. (2019, December 5). Alexander Hamilton, the Other Tariff Man Who Created a Mess. The Daily Economy. Retrieved from https://thedailyeconomy.org/article/alexander-hamilton-the-other-tariff-man-who-created-a-mess/

- Rechenberg, A. (2024, October 21). How Tariffs Benefit the Working Class and Reduce Income Inequality. Coalition for a Prosperous America. Retrieved from https://prosperousamerica.org/how-tariffs-benefit-the-working-class-and-reduce-income-inequality/

- The White House. (2025, February 1). Fact Sheet: President Donald J. Trump Imposes Tariffs on Imports from Canada, Mexico and China. Retrieved from https://www.whitehouse.gov/fact-sheets/2025/02/fact-sheet-president-donald-j-trump-imposes-tariffs-on-imports-from-canada-mexico-and-china/

- Wall Street Journal. (2023, December 28). Biden Struggles to Push Trade Deals with Allies as Election Approaches. (Y. Hayashi). Wall Street Journal. (Referenced via Wikipedia: History of tariffs in the United States).